January 2015, Unfold

won the

Henry

van de Velde Award for Young Talent.

Tamar Shafrir wrote an

excellent essay about Unfold for the catalogue accompanying the

exhibition at Bozar in Brussels. Click

More... to

read the whole essay or download here:

Reinventing

the Wheel (Dutch and English)

"Grace Murray Hopper, one of the first computer programmers at

Harvard University, used to tell the story of debugging the Mark II

Aiken Relay Calculator, an electromechanical computer. The problem

was traced to Relay #70 on Panel F, where the operators discovered

an intruder in the system. The event was duly recorded in the log

on 9 September 1947: “First actual case of bug being

found,” written below a moth taped to the paper.

The anecdote reveals something that has largely been forgotten as

digital technology became pervasive, microscopic, and black-boxed

beneath impenetrable glass and aluminium. The computer of 1947,

assembled at an architectural scale—18 metres in length, with

a 2.5-metre-high front panel—retained not only an

overwhelming sense of material physicality but also a sensitivity

to the capricious behaviours of its environment and the organic

bodies contained therein. Though the machine operated by different

logics, it was entirely ensconced within a natural system of chance

encounters, sparks, fumbles, and the odd winged creature.

Design itself has struggled with this precarious membrane between

the analogue and digital realms, although its initial confrontation

with that frontier is difficult to locate precisely. The onset of

industrial production, for example, could be considered the first

step towards a reproducible script, oblivious to the individual

authorship of the various figures involved in its manufacture, but

it might equally be seen as a mere progression of the repetitive

motor skills of the disciplined craftsman. The 1960s and ‘70s

breakthroughs in 3D modelling, from the wire-frame Boeing man to

real-time drawing in a graphic interface, tread a similarly

equivocal line between mathematical representation and design.

Still, as in the moth, the shift into the digital realm produced

several conclusive artefacts that can be used to mark its

borders.

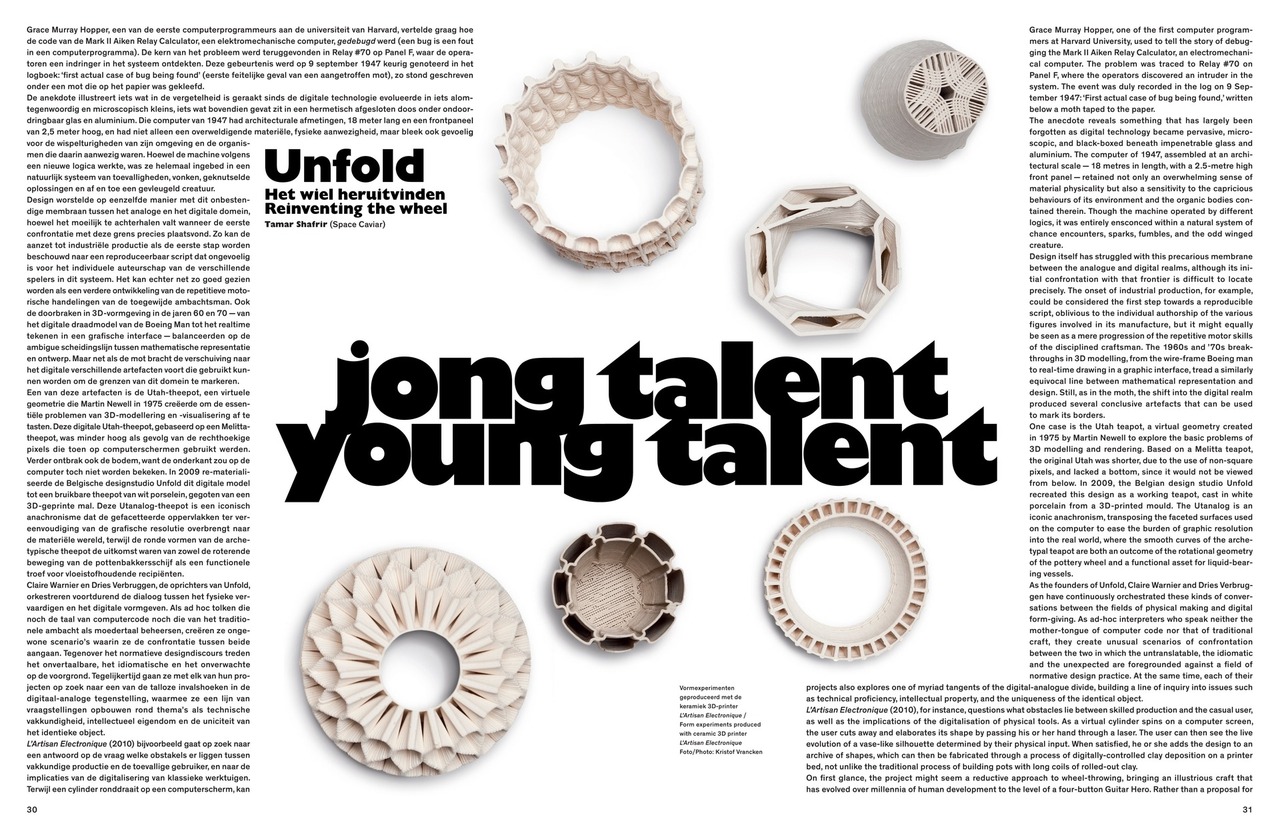

One case is the Utah teapot, a virtual geometry created in 1975 by

Martin Newell to explore the basic problems of 3D modelling and

rendering. Based on a Melitta teapot, the original Utah was

shorter, due to the use of non-square pixels, and lacked a bottom,

since it would not be viewed from below. In 2009, the Belgian

design studio Unfold recreated this design as a working teapot,

cast in white porcelain from a 3D-printed mould. The Utanalog is an

iconic anachronism, transposing the faceted surfaces used on the

computer to ease the burden of graphic resolution into the real

world, where the smooth curves of the archetypal teapot are both an

outcome of the rotational geometry of the pottery wheel and a

functional asset for liquid-bearing vessels.

As the founders of Unfold, Claire Warnier and Dries Verbruggen have

continuously orchestrated these kinds of conversations between the

fields of physical making and digital form-giving. As ad-hoc

interpreters who speak neither the mother-tongue of computer code

nor that of traditional craft, they create unusual scenarios of

confrontation between the two in which the untranslatable, the

idiomatic and the unexpected are foregrounded against a field of

normative design practice. At the same time, each of their projects

also explores one of myriad tangents of the digital-analogue

divide, building a line of inquiry into issues such as technical

proficiency, intellectual property, and the uniqueness of the

identical object.

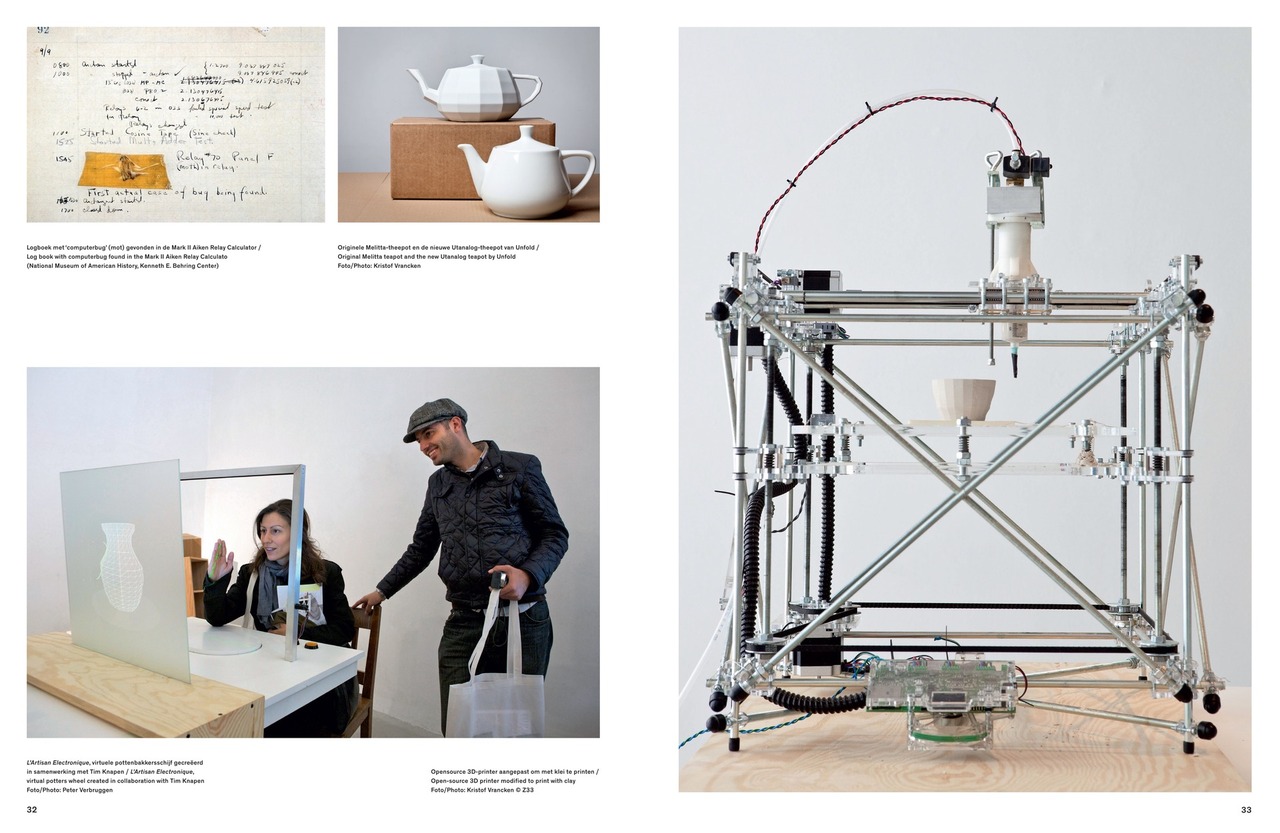

L’Artisan Electronique (2010), for instance, questions what

obstacles lie between skilled production and the casual user, as

well as the implications of the digitalisation of physical tools.

As a virtual cylinder spins on a computer screen, the user cuts

away and elaborates its shape by passing his or her hand through a

laser. The user can then see the live evolution of a vase-like

silhouette determined by their physical input. When satisfied, he

or she adds the design to an archive of shapes, which can then be

fabricated through a process of digitally-controlled clay

deposition on a printer bed, not unlike the traditional process of

building pots with long coils of rolled-out clay.

On first glance, the project might seem a reductive approach to

wheel-throwing, bringing an illustrious craft that has evolved over

millennia of human development to the level of a four-button Guitar

Hero. Rather than a proposal for mainstream consumer production,

however, L’Artisan Electronique is actually a set of layered

premises that challenge preconceptions about both handcraft and

digital design. For the first-time user, the tool does have a more

gentle learning curve than the pottery wheel, where the desired

form must combat the overriding factors of clay consistency,

moisture, temperature, speed, and the strength and dexterity of the

human hand as well as its extensions (knives, ribs, and wires).

However, it is much more difficult to create the perfect symmetry

that comes so readily in 3D modelling programmes, and the complex

faceted surfaces produced on the virtual wheel are more the

byproduct of human imperfection than the demonstration of digital

sophistication. Furthermore, Unfold’s design dispenses with

the electronic palette of discrete digital tools (Boolean

operations, extrusion, scaling, and tweening, among many others)

for an indeterminate spectrum of manual manipulations of a virtual

solid. Finally, the project introduces a new dynamic of creation:

deprived of the resistance of wet clay, even the master’s

hand may find a new challenge in moulding thin air.

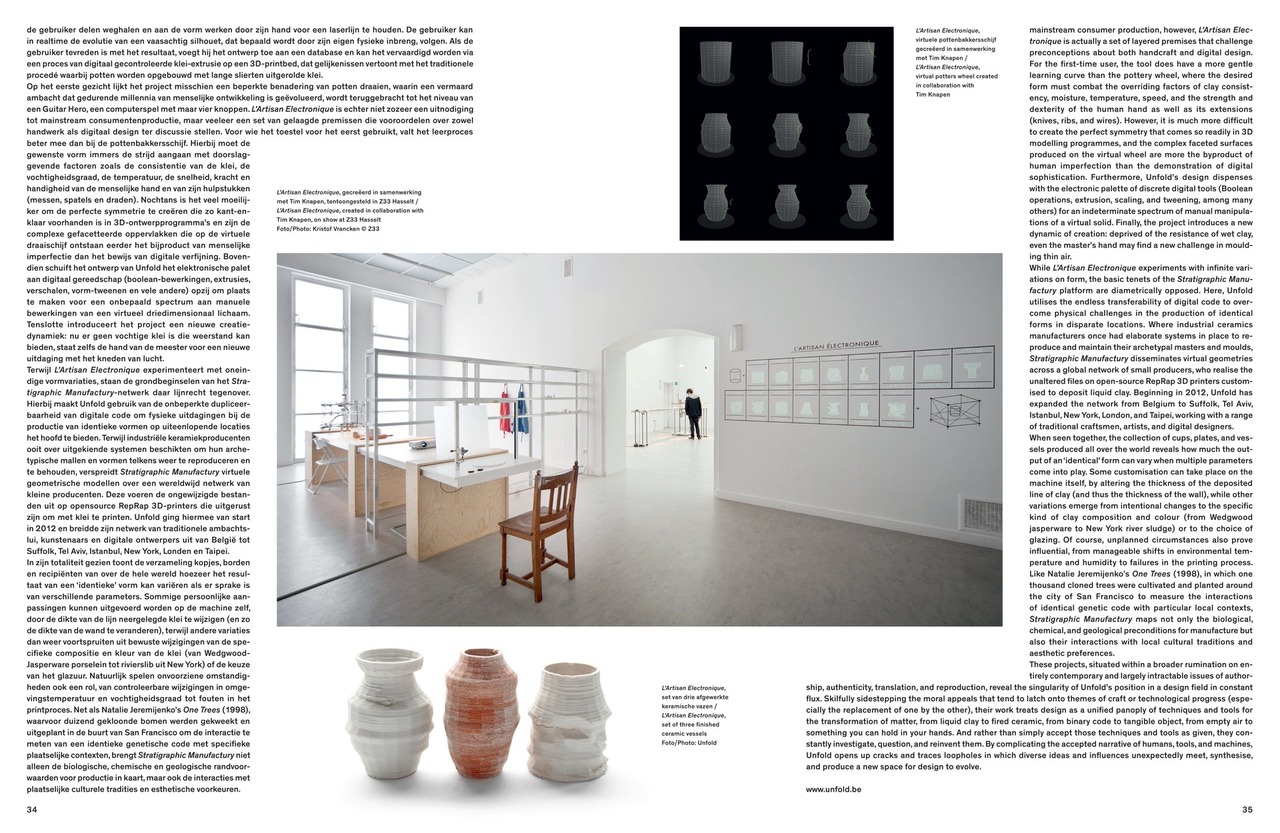

While L’Artisan Electronique experiments with infinite

variations on form, the basic tenets of the Stratigraphic

Manufactury platform are diametrically opposed. Here, Unfold

utilises the endless transferability of digital code to overcome

physical challenges in the production of identical forms in

disparate locations. Where industrial ceramics manufacturers once

had elaborate systems in place to reproduce and maintain their

archetypal masters and moulds, Stratigraphic Manufactury

disseminates virtual geometries across a global network of small

producers, who realise the unaltered files on open-source RepRap 3D

printers customised to deposit liquid clay. Beginning in 2012,

Unfold has expanded the network from Belgium to Suffolk, Tel Aviv,

Istanbul, New York, London, and Taipei, working with a range of

traditional craftsmen, artists, and digital designers.

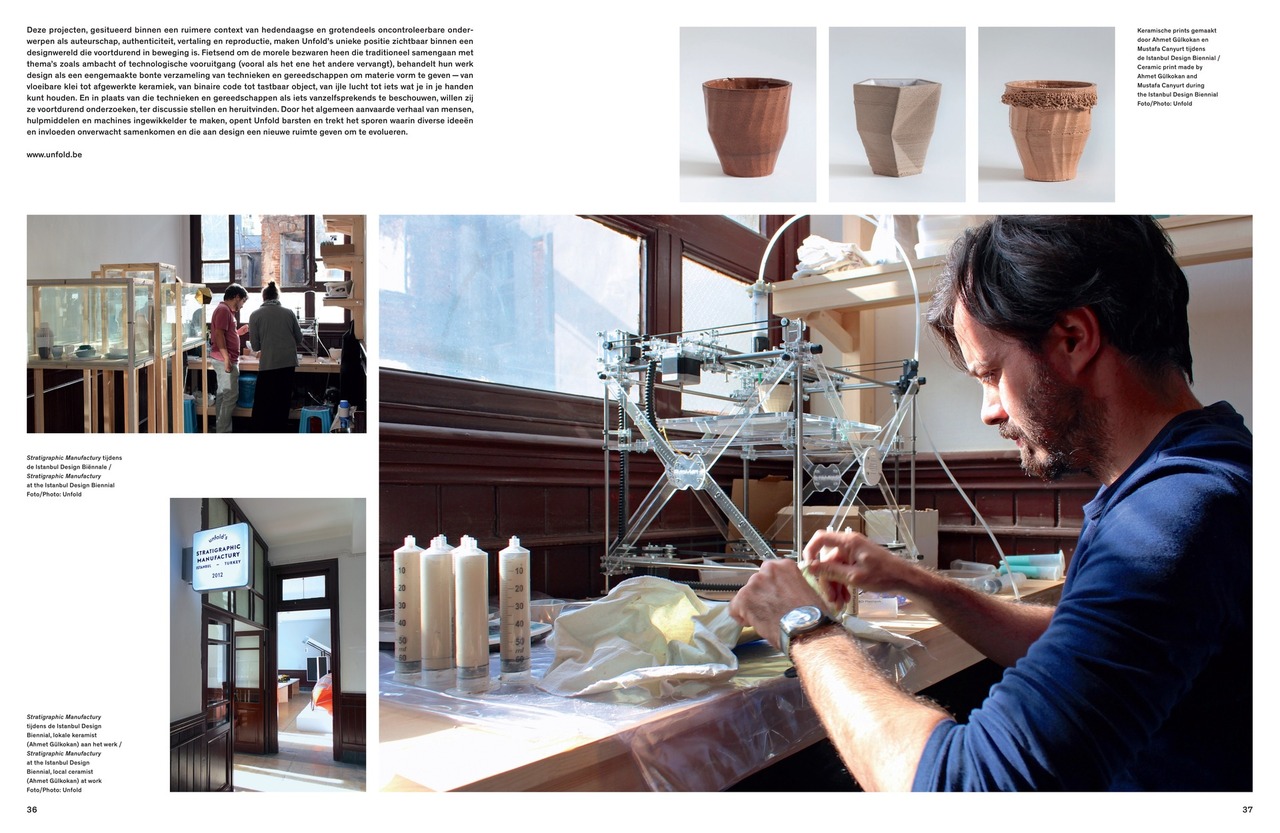

When seen together, the collection of cups, plates, and vessels

produced all over the world reveals how much the output of an

“identical” form can vary when multiple parameters come

into play. Some customisation can take place on the machine itself,

by altering the thickness of the deposited line of clay (and thus

the thickness of the wall), while other variations emerge from

intentional changes to the specific kind of clay composition and

colour (from Wedgwood jasperware to New York river sludge) or to

the choice of glazing. Of course, unplanned circumstances also

prove influential, from manageable shifts in environmental

temperature and humidity to failures in the printing process. Like

Natalie Jeremijenko’s One Trees (1998), in which one thousand

cloned trees were cultivated and planted around the city of San

Francisco to measure the interactions of identical genetic code

with particular local contexts, Stratigraphic Manufactury maps not

only the biological, chemical, and geological preconditions for

manufacture but also their interactions with local cultural

traditions and aesthetic preferences.

These projects, situated within a broader rumination on entirely

contemporary and largely intractable issues of authorship,

authenticity, translation, and reproduction, reveal the singularity

of Unfold’s position in a design field in constant flux.

Skilfully sidestepping the moral appeals that tend to latch onto

themes of craft or technological progress (especially the

replacement of one by the other), their work treats design as a

unified panoply of techniques and tools for the transformation of

matter, from liquid clay to fired ceramic, from binary code to

tangible object, from empty air to something you can hold in your

hands. And rather than simply accept those techniques and tools as

given, they constantly investigate, question, and reinvent them. By

complicating the accepted narrative of humans, tools, and machines,

Unfold opens up cracks and traces loopholes in which diverse ideas

and influences unexpectedly meet, synthesise, and produce a new

space for design to evolve."

contact

contact